America’s Top 10 Conservation Heroes is a series honoring the individuals and organizations that have made the biggest mark on conservation, environmental protection, and awareness of the outdoors. The series is written by Charles Wilkinson, Distinguished Professor at the University of Colorado and author of fourteen books on law, history, and society in the American West.

Jump to:

1. Theodore Roosevelt 2. John Muir

3. Rachel Carson 4. Stewart Udall

5. Aldo Leopold 6. Ansel Adams

7. Earthjustice 8. Henry David Thoreau

9. Edward Abbey 10. Bruce Babbitt

Then, now, and forever, TR will always be first. Through the creation of federal forests, parks, monuments, wildlife preserves, and other actions, he gave Americans the world’s greatest conservation system.

When Roosevelt came to office in 1901, the central force in government policy was still the “Great Bar-B-Q,” the policy of throwing the public lands open for unfettered development. There were stirrings of an environmental consciousness, such as the creation of Yellowstone and Yosemite National Parks, but the enlightened Progressive Era was still in its infancy. It took a bold and foresighted president to ignite what amounted to nothing short of a revolution.

TR possessed a virtually undiluted power (probably not intended as such by the 1891 Congress) to create national forests out of the public domain. Presidents Harrison and Cleveland had used it previously, but Roosevelt took it to a whole new level by setting aside 150 million acres, about 7% of all land in the country, as forest preserves.

The policies and spirit of the Roosevelt Administration were on grand display in March 1907. The President, with the Chief Forester Gifford Pinchot at his side, had enraged western politicians the previous five years by unilaterally proclaiming more than a hundred national forests. Now Congress was about to bring him up short by shutting down his power under the once-minor 1891 provision. The House and Senate approved a measure that would block him from declaring new national forests in Oregon, Washington, Idaho, Montana, Idaho, and Wyoming, the states where the outcries were the loudest. Roosevelt’s opponents strategically embedded the measure in the general appropriations bill, which the President would have no choice but to approve.

But an event intervened. For some reason, the appropriations bill found its way to the bottom of TR’s “bills to sign” pile. This may have been related to the activities of the full, frenzied, and celebratory previous week, when Roosevelt, Pinchot, and his men laid out maps of western states on the floor and drew boundary lines around national forest candidates. The President himself had gotten down on his hands and knees to check out the topography.

So, when it came to signing time, before he could get to the appropriations bill at the bottom of the pile, he just happened to sign a raft of executive orders, 38 in all, creating still more national forests totaling no less than 16 million acres—one-quarter the size of Colorado. Only then did the president turn to approving the law that abrogated his authority in the six listed states. For TR, who so loved to inject drama—and joy—into the making of public policy, signing the “Midnight Reserves” was one of his most cherished moments. He laughed that his opponents “turned handsprings in their wrath.” “Oh,” he exulted, “this is bully!”

TR, who treasured birds ever since he was a boy, grieved at the extermination of the passenger pigeons and other species. He knew many more were at risk. The extinction of birds, he wrote, “is like the loss of a gallery of the artists of old time.” “Wild beast and birds,” he said on another occasion, “are by right not the property merely of the people who are alive today, but the property of unknown generations, whose belongings we gave no right to squander.

In March 1903, Roosevelt swung into action. He notified the Attorney General of his desire to declare Pelican Island, off the coast of Florida, as a federal wildlife refuge. He knew that, unlike the national forests, he had no statute authorizing the creation of wildlife refuges. Indeed, there had never been such a thing as a wildlife refuge.

A few days later, a government attorney came to the White House to deliver the legal opinion of the Justice Department. He solemnly intoned that “I cannot find any law that will allow you to do this, Mr. President.”

“But,” replied TR, rising to his full height, “is there a law that will prevent it?” The lawyer, now frowning, replied that there was not. The President responded, “very well. I so declare it.”

Pelican Island Wildlife Refuge—one congressman pronounced it “the fad of game preservation run start raving mad”—became the first of 55 wildlife preserves declared by Roosevelt. They have since been joined by 500 others, at least one in every state, to constitute today’s National Wildlife Refuge System.

The Antiquities Act of 1906 grants presidents authority to create national monuments, similar to national parks. The bill was the brainchild of Edgar Lee Hewett, an archaeologist who wanted to allow presidential set asides of small areas of land in order to protect ancient Indian villages and relics in the Southwest from grave robbers. In order to put a ceiling on the size of these national monuments, the statute set a maximum size of “the smallest area practicable,” words that seem highly restrictive but amounted to a wide open door to the full-speed-ahead president.

Within months, TR made use of this power, establishing national monuments at Devils Tower in Wyoming; El Morro, Montezuma Castle, Petrified Forest, and Chaco Canyon in Arizona and New Mexico; and elsewhere. But what of the “smallest area practicable” limitation for a President who was not much enthused by limitations? Well, John Muir had implored TR to visit a certain gorge in Arizona….

And so Roosevelt reflected on the Grand Canyon and found that, under these circumstances, the smallest area practicable could be quite expansive indeed. On January 11, 1908, he designated much of the Canyon as a national monument. "Let this great wonder of nature remain as it now is,” he declared. “You cannot improve on it. But what you can do is keep it for your children, your children’s children, and all who come after you, as the one great sight which every American should see."

TR proclaimed 18 national monuments in all. Especially with the designation of the Grand Canyon, he left future presidents with a powerhouse of a statute whose words are so modest. Later presidents, acting unilaterally without needing congressional approval under the Antiquities Act, have been able to conserve vast landscapes, most notably in Alaska and the Southwest.

You will hear people say that it is an historical accident that the most capitalistic nation in the world holds so much government land. It is no historical accident. It was a central aim of the Progressives and their leader, Theodore Roosevelt. They believed to their depths that large blocks of lands, many of them America’s glory lands, must remain forever public, open to the people. That’s why they created so many federal parks, forests, monuments, and wildlife preserves and set up agencies and regulations to ensure their protection. Yes, permanent federal protection was and still is the core policy and it is due, first and foremost, to the brave and visionary president who gave his nation a gift for the ages—his age, our age, and every age to follow.

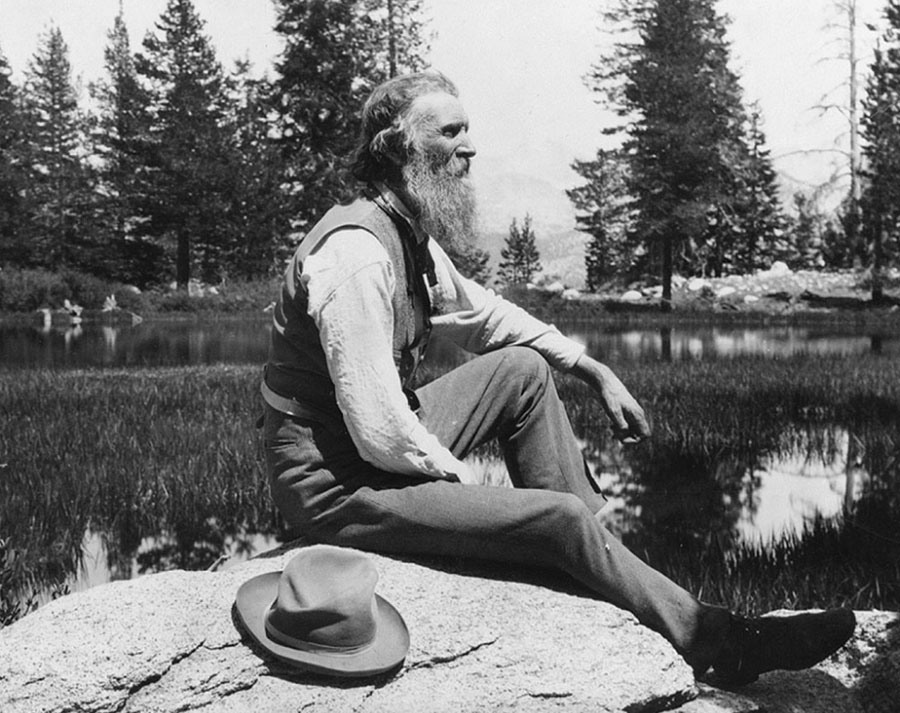

John Muir, honored scientist, outdoorsman extraordinaire, influential writer, and passionate, irrepressible activist, changed the world in ways that continue to make our lives better and richer a century later.

Muir, a child prodigy who won blue ribbons for his inventions at the Wisconsin State Fair, studied botany and other subjects at the University of Wisconsin for three years but the indoors could not hold him. He and his brother ventured up to Canada to explore the woods of Ontario. Then, in 1868 at the age of 29, having just finished a 1,000-mile hike from Indiana to Florida, he stepped off a steamship onto the San Francisco wharf and asked directions to “any place that is wild.” He went straight to the Sierra Nevada, which captured his imagination upon his first visit:

“Then it seemed to me that the Sierra should be called, not the Nevada or Snowy Range, but the Range of Light. And after ten years of wandering and wondering in the heart of it, rejoicing in its glorious floods of light, the white beams of the morning streaming through the passes, the noonday radiance on the crystal rocks, the flush of the alpenglow, and the irised spray of countless waterfalls, it still seems above all others the Range of Light.”

He immersed himself in the Sierra Nevada, which he loved so, building a base of knowledge through years of hikes of 20-40 miles a day. Muir proved, contrary to the views of Josiah Whitney, the giant of California geology, that Yosemite Valley and its environs had been crafted by glaciers. He understood the yet unnamed science of ecology—“ We all travel the Milky Way together, trees and men,” “Everything is bound fast by a thousand invisible cords”—and generations later was made a charter inductee into the Ecology Hall of Fame.

Although he had not planned on it, Muir became a prodigious writer (his Collected Works filled up ten volumes). By the early 1880s, his evocative articles and books, drawn from his vigorous treks in Yosemite and north to Alaska and south to the Grand Canyon, drew a large and enthusiastic national audience. His adventures, such as one in a violent high Sierra windstorm when he chose to climb to the top of a fir tree 100 feet tall, were hard to resist:

“Never before did I enjoy so noble an exhilaration of motion. The slender tops fairly flapped and swished in the passionate torrent, bending and swirling backward and forward, round and round, tracing indescribably combinations of vertical and horizontal curves, while I clung with muscles firm braced, like a bobolink on a reed... I was … safe, free to take the wind into my pulses and enjoy the excited forest from my superb outlook.”

Muir’s readers enjoyed his writing as literature, but he also was whipping up support for conservation. He made wilderness exciting and an object of great worth. At the same time, the land—including his beloved Sierra—was suffering from insults such as logging of giant redwoods and excessive grazing of sheep, which he called “hoofed locusts.”

In 1889, Muir invited an easterner, Robert Underwood Johnson, editor of Century magazine, out to Yosemite for a visit. Muir showed him the glories and wounds of the Yosemite country and explained that Congress had given it to the State of California in 1864 but that the state was not protecting the land. Congress should take it back. Underwood agreed, and Muir wrote articles urging protection of Yosemite for Johnson’s magazine and newspapers. Within a year Congress created Yosemite National Park.

The 1890 Yosemite statute was an historic moment. In 1872 Congress had designated Yellowstone National Park, the first national park in world history (western writer Wallace Stegner has called our national parks “the best idea we ever had” and today every country has national parks). But, as of 1890, Yellowstone still stood alone. The creation of Yosemite reinvigorated the park idea and many more were established in the years to come. Rightly called “the Father of the National Parks,” Muir’s words and actions led to the creation of Grand Canyon, Sequoia, Petrified Forest, Rainier, Glacier Bay, and others.

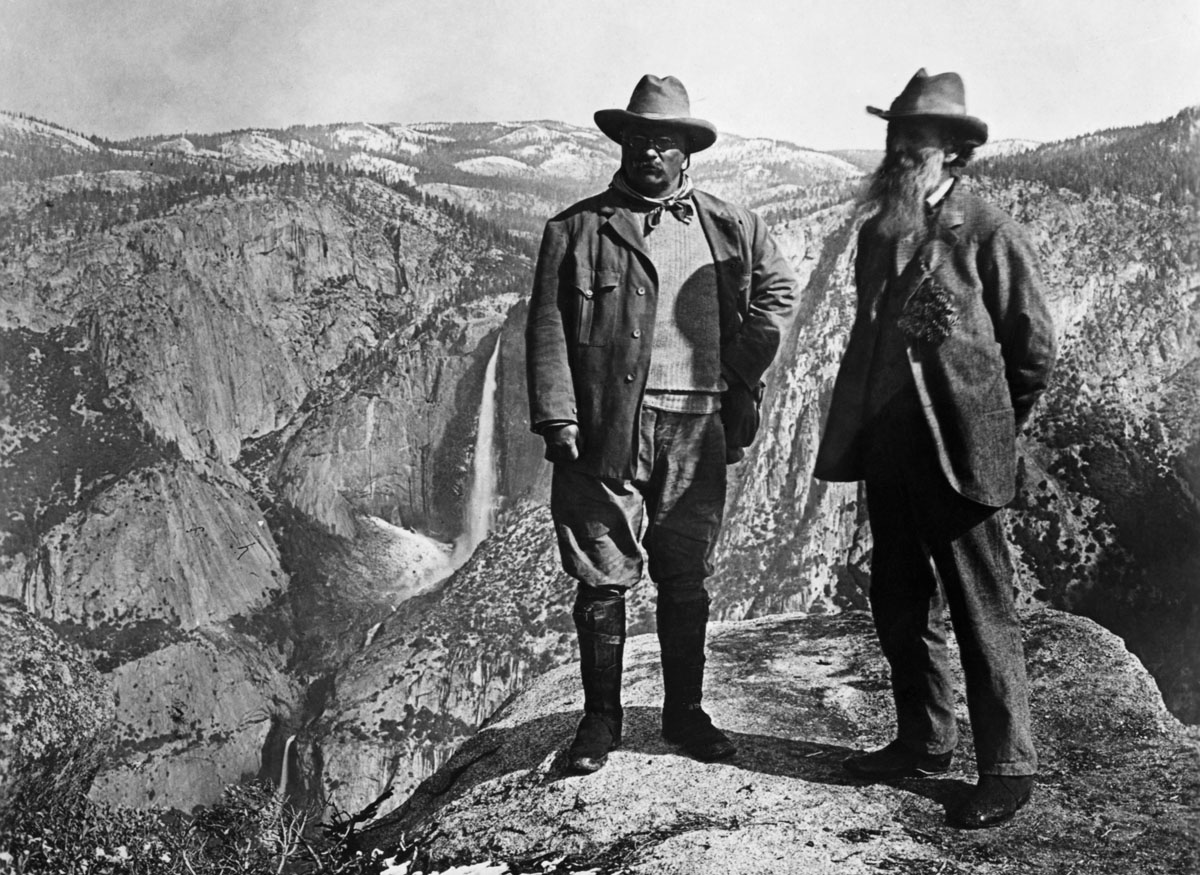

President Theodore Roosevelt knew Muir’s writing and career well and wanted to meet him on a trip to the West in 1903. Knowing of TR’s love of the outdoors, Muir was enthusiastic about it as well (as compared to the earlier visit from Ralph Waldo Emerson, whom he judged to be an “indoor philosopher”). They went in to Glacier Point, as TR reported it, with ”a couple of packers and two mules to carry our tent, bedding, and food for a three day trip.” The two men broke off from the packers and slept under the stars. The President was rhapsodic: “The first night was clear, and we lay down in the darkening aisles of the great Sequoia grove. The majestic trunks, beautiful in color and in symmetry, rose round us like the pillars of a mightier cathedral than ever was conceived even by the fervor of the Middle Ages.”

Muir wanted TR to see the magnificence of the place but also “to do some forest good in talking freely around the campfire." He had three agenda items. At the time presidents had power to designate national forests and put them beyond the reach of the timber barons. Roosevelt already had declared some national forests but Muir believed there should be many more:

“Any fool can destroy trees. They cannot run away; and if they could, they would still be destroyed, chased and hunted down as long as fun or a dollar could be got out of their bark hides, branching horns, or magnificent bole backbones. Few that fell trees plant them; nor would planting avail much towards getting back anything like the noble primeval forests. … God has cared for these trees, saved them from drought, disease, avalanches, and a thousand straining, leveling tempests and floods, but he cannot save them from fools — only Uncle Sam can do that.”

Muir also wanted have Yosemite Valley and Mariposa Grove returned to the United States and placed in the Park (in the bargaining over the 1890 statute creating the Park, California had agreed only to have the high country included in the Park). Finally, he urged TR to visit the Grand Canyon and have it protected. All three of Muir’s objectives came to pass as a result of this literally unique lobbying session.

John Muir grieved at the setback that came near the end of his life. San Francisco, seeking to expand its water supplies, pressed for a storage reservoir in the Sierra. The landscape to be inundated was Hetch Hetchy, a magnificent valley just to the the north of Yosemite and often referred to as Yosemite’s “sister valley.” The Sierra Club, founded by Muir in 1892, furiously opposed the project for ten years and generated significant public support. Nonetheless, in 1913 the Raker Act allowed the flooding to go ahead. Muir passed away the next year at the age of 76. Some of his friends and colleagues believed he died of sorrow or a broken heart over the loss of Hetch Hetchy.

In 1916, Congress passed the National Park Service Act, long the dream of John Muir. The statute established the National Park Service as a professional land management agency and enacted a comprehensive mission for the parks, which previously had operated independently and often haphazardly. The Park Service’s mission for these landscapes—“the Nation’s crown jewels”—is to “leave them unimpaired for the enjoyment of future generations,” a standard that surely reflects and honors the life journey of The Father of the National Parks.

Rachel Carson, with her scientific expertise, compelling writing, and unflagging courage, sparked the nation and took it in a new direction in terms of fighting pollution and protecting the environment.

Born in 1907, Carson grew up in rural Pennsylvania and, as a young girl with a love of the outdoors, wanted to be a writer and make nature’s creatures “as alive to others as they are to me.” After majoring in biology and earning a masters in zoology from Johns Hopkins University, and facing professional roadblocks against women in the sciences, she took a position as a science writer at the U.S. Bureau of Fisheries, where she wrote many articles and soon was elevated to editor-in-chief of publications.

Carson wrote three early and extraordinary books, Under the Sea-Wind (1941), The Sea Around Us (1952), and, after leaving the Bureau of Fisheries to pursue fulltime writing, The Edge of the Sea (1955). The last two became bestsellers and The Sea Around Us won the National Book award. One observer called these works, at once scientifically precise and beautifully written, a “biography “ of the Atlantic Ocean.

By 1958, Carson, now a well-known and highly regarded scientist, was working on a new and far-reaching project. For years, she had wondered about the connection between pesticides, especially DDT, and cancer, and spent increasing amounts of time researching the subject. Now the evidence of the impacts on human health and lives had mounted, and she felt she had no choice but to go public with it, writing that “It was pleasant to believe that much of Nature was forever beyond the tampering reach of man: I have now opened my eyes and my mind. I may not like what I see, but it does no good to ignore it."

These would be difficult years for her. Carson’s niece had died and she became legal guardian of her grandnephew, age 5. Carson, who lived alone, also had to care for and support her aging and ailing mother. Carson’s own health took a turn for the worse. Breast cancer was diagnosed and required radiation.

Then the magnitude of the DDT project, coupled with the anger and aggressiveness of industry, intensified the pressure on the modest, soft-spoken Carson. The chemical companies had learned of her work and leapt into action, unleashing an all-out attack in an effort to prevent the publisher, Houghton Mifflin, from releasing the book. As Time magazine reported:

“Carson was violently assailed by threats of lawsuits and derision, including suggestions that this meticulous scientist was a "hysterical woman" unqualified to write such a book. A huge counterattack was organized and led by Monsanto, Velsicol, American Cyanamid—indeed, the whole chemical industry—duly supported by the Agriculture Department as well as the more cautious in the media.”

Yet neither the author nor her publisher relented. Carson’s epic, Silent Spring, after being serialized in The New Yorker, was published in 1962. The book ‘s conclusions were too accurate, too careful—too powerful—for the chemical companies to overcome. Carson documented the effects of DDT and other chemicals clinically and in detail. Her writing was also often lyrical. In addition to detailing the impacts on humans, she imagined a future silent spring:

“There is a strange stillness. The birds, for example, where had they gone? ... It was a spring without voices. On the mornings that had once throbbed with the dawn chorus of robins, catbirds, doves, jays, wrens, and scores of other bird voices there was now no sound; only silence lay over the fields and woods and marsh.”

Silent Spring, widely read, resonated with scientists, political leaders, public officials, and the American people generally. It spoke both to specific issues of DDT and, broadly, to the callous disregard that humans too often showed toward the natural world. President Kennedy endorsed the book at a press conference and appointed an investigative committee, which in time issued an influential report; Earth Day was born in 1970; the use of DDT was banned in the United States in 1972; the Clean Water Act, Clean Air Act, and numerous other pollution laws were enacted in the 1970s; Silent Spring was acclaimed as one of the most important books of the 20th century and Time magazine listed Carson as one of the 100 most influential people in the 20th century. Rachel Carson lived to testify on her findings in front of Congress but died of cancer in 1964 at the age of 56.

The publication of Silent Spring in 1962 is as good a place as any to mark the beginning of the modern environmental consciousness and movement.

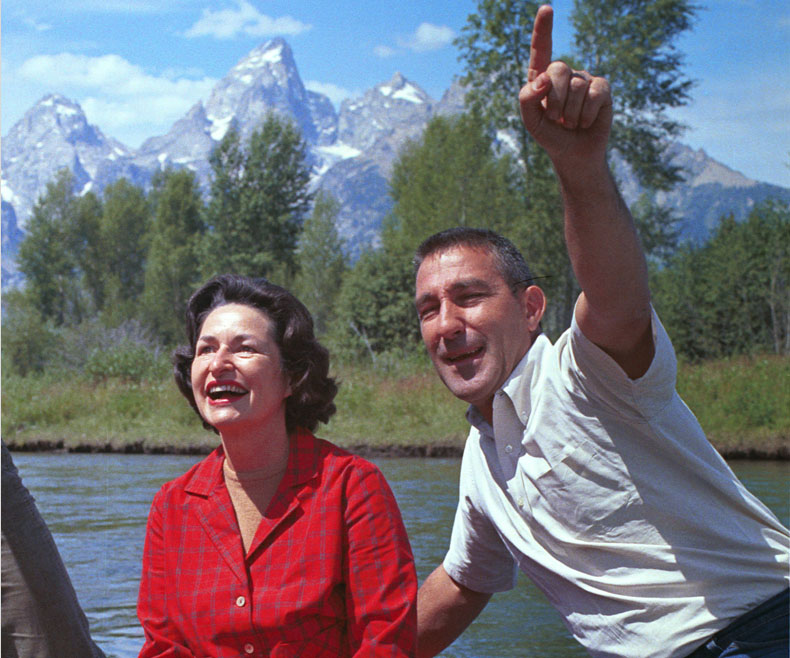

The most successful of all secretaries of the interior, Stewart Udall was born in 1920 in St. Johns in remote eastern Arizona. “I feel, looking back over my life, that I actually grew up in the nineteenth century. It was still the frontier.” Coming from a public-spirited farm family, he loved the land and wanted to serve. In 1954 he ran for Congress and won.

When President Kennedy appointed him Secretary of the Interior in 1961 (the first Arizonan to hold a cabinet-level position), the idealistic young secretary took on a rare and daunting task—to write a book while in office. He burned the midnight oil and in two years completed The Quiet Crisis, both a history of conservation and a powerful moral call for Americans to protect the land and waters from the ravages of development and pollution. Coming just a year after Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring, Udall’s book fit beautifully with hers (the two became close friends) in heralding a new age of environmentalism.

Udall served during the height of the Big Buildup, the furious development rampage of the Post-World War II years in which industry and the booming western cities joined together to carry out water and energy development of unprecedented magnitude. An activist secretary heading up a department that had previously been captured the developers, he had to draw upon every last bit of vision, determination, and courage he could muster. Udall reformed key provisions in the badly outdated Hardrock Mining Law of 1872. He played a major role in conceiving and enacting the Wild and Scenic Rivers Act of 1968. Udall proposed and achieved all manner of congressional and presidential land preservation areas, including three national parks, six national monuments, eight national seashores and lakeshores, and 56 national wildlife refuges.

Some of his best work was done in the canyon country of the Southwest. In 1961, Floyd Dominy, the able and messianic commissioner of reclamation who never saw a dam-and-reservoir project he didn’t like, was perhaps the most powerful person in the American West. His favorite project at the time was “Junction Dam,” just below the Confluence, glory country where the Colorado and Green rivers come together. The resulting reservoir—a goliath that would have inundated 93 miles of the Colorado, 109 miles of the Green, and the town of Moab—would have been far and away the largest water project in the Colorado River watershed. Udall and Dominy were at a meeting in Page, Arizona and Dominy, anxious to gain the support of the new secretary, offered Udall a ride back to Washington in his government plane to show him the Junction Dam site. (One of Udall’s reactions was, “So the reclamation commissioner has his own plane but the goddammed secretary doesn’t?!!”)

For once, Dominy was unable to control an interior secretary. When the plane got to the proposed dam site, Udall saw something else. “I saw the Needles and all those monuments and formations and all the rest. I didn’t say anything to Dominy, but to myself I thought, ‘God almighty, that’s a national park!’ ” By 1964, Congress established Canyonlands National Park, the largest in Utah, and the Junction Dam proposal was consigned to the trash heap.

By the mid-1960s, times were changing but Dominy was still riding high and kept another mega-project alive: he wanted to construct two dams in the Grand Canyon. Dominy had powerful support from the cities and industries pushing the Big Buildup. David Brower of the Sierra Club organized a furious campaign against the idea: ridiculing Dominy’s argument that the dams would be good for recreation (the true reason was energy production), Brower asked, “Should we flood the Sistine Chapel so tourists can get closer to the ceiling?” Facing political heat from dam supporters, including some from the Lyndon Johnson White House, Udall took his time making a decision, but privately made up his mind in 1967. He decided to take an “investigatory” float trip down through the Grand Canyon —and told his staff that he wanted the trip to be run by the National Park Service, not Dominy’s office. After seeing the wonders of the Canyon (he’d never floated it before), he put all of his ducks in order and announced that the Johnson Administration was withdrawing its support for the dams. The projects were dead.

After leaving office in 1969, Udall was a model of public service. He spoke out on public issues in three books and numerous op-ed pieces and speeches. One of the best parts of his legacy is his 30-year crusade for justice for the widows of Navajo uranium miners and atomic test fallout “Downwinders.” These were the people and land that he loved, and his dogged litigation and arguments to Congress exposed previously secret documents and the hideously callous indifference of the mining companies and government and military officials to the cancers, death and disfigurement caused by the radioactivity. "Where I come from, if you take on a job, you finish it," Udall said. "Particularly when you look at the tragedy inflicted on these people--I just couldn't let it go."

Udall passed away in 2010. That same year, Congress passed legislation, signed by President Obama, renaming the Main Interior Building in Washington, DC, the “Stewart Lee Udall Department of the Interior Building.” The honor was widely cheered, for Udall had set the interior department on a new course. As one person put it, “If you've ever enjoyed a national park, hiked down a trail, backpacked into wilderness, or paddled a wild and scenic stream, pause and give a minute of thanks for Stewart L. Udall.”

Aldo Leopold, wilderness advocate and author of the most influential book on conservation, was born in 1887, grew up in Iowa near the bluffs of the Mississippi River, and was captivated by the land from the beginning. He attended Yale Forestry School—the hotbed of conservation at the time—and after graduation joined the newly-minted Forest Service. Assigned to the Southwest, he rose quickly in the agency, writing many scientific and philosophical articles and earning appointment as a ranger.

Leopold saw the development that was coming on strong and became a committed advocate for wilderness—“Of what avail are forty freedoms without a blank spot on the map?” In 1924 he made conservation history by spearheading the Forest Service’s designation of 500,000 acres of federal land as the Gila Wilderness Area in New Mexico. It was the first time that any government in the world had ever designated land as wilderness (this led to the Wilderness Act of 1964, the first legislative declaration of wilderness in history).

In 1928 Leopold left government service and joined the University of Wisconsin faculty, where he was named to the new chair in game management. He wrote hundreds of scholarly articles, always on the land, water, wildlife, and wilderness. He and seven other leading conservationists founded the Wilderness Society in 1935. In the same year, the family purchased a run-down farm on the Wisconsin River that the Leopolds brought back to life. The farm inspired Leopold’s surpassingly great book, A Sand County Almanac.

In it, he put down some of the most memorable passages in all of American literature. He wrote of a visit in the 1920s to the “green lagoons” at the mouth of the Colorado River, across the international line in Mexico. “A verdant wall of mesquite and willow separated the channel from the thorny desert beyond.” He described the lush vegetation and animals of all sorts, among them egrets, cormorants, mallards and teal, bobcats, coyotes, and raccoons—and, most of all, “the despot of the Delta, the great jaguar, el tigre.” He continued:

“We saw neither hide nor hair of him, but his personality pervaded the wilderness; no living beast forgot his potential presence, for the price of unwariness was death. No deer rounded a bush, or stopped to nibble pods under a mesquite tree, with out a premonitory sniff for el tigre. No campfire died without talk of him. No dog curled up for the night, save at his master’s feet; he needed no telling that the king of cats still ruled the night; that those massive jaws could fell an ox, those jaws shear off bones like a guillotine.”

But Leopold was writing in the 1940s, a generation after that visit, and he knew that the wilderness—and el tigre—were no more. “By this time the Delta has probably been made safe for cows, and forever dull for adventuring hunters. Freedom from fear has arrived, but a glory has departed from the green lagoons.”

Leopold also mourned the loss of wildness in a passage called “Thinking like a Mountain.” Wolves announced their presence when “A deep chesty howl echoes from rimrock to rimrock, rolls down the mountain, and fades into the far darkness of the night. It is an outburst of wild defiant sorrow, and of contempt for all the adversities of the world.” “Only the mountain,” he wrote, “has lived long enough to listen objectively to the howl of a wolf.” Leopold was a hunter, an ethical one, and his ethic grew much deeper the day he shot an aged female wolf on the slope of the mountain:

“We reached the old wolf in time to watch a fierce green fire dying in her eyes. I realized then, and have know ever since, that there was something new to me in those eyes—something known only to her and the mountain. I was young then, and full of trigger-itch; I thought that because fewer wolves meant more deer, that no wolves would mean hunters’ paradise. But after seeing the green fire die, I sensed that neither the wolf nor the mountain agreed with such a view.”

In A Sand Country Almanac, Leopold announced the “land ethic” that has been so influential in causing millions of readers in America and around the world to understand the relationship of our species to the land. A powerfully written book drawing upon “The Green Lagoons,” “Thinking Like a Mountain,” and many other personal and profound experiences in nature, it deserves multiple readings by all who care for, and worry about, the land.

Leopold’s land ethic is at once sweeping and general, layered and nuanced, cautionary and uplifting. It is founded on ecology: “Land… is not merely soil; it is a fountain of energy flowing through a circuit of soils, plants, and animals”; the role of Homo sapiens is not “the conqueror of the land-community” but rather being “a plain member and citizen of it.” The land ethic abhors species extinctions and honors species diversity: “The first rule of intelligent tinkering is to save all the pieces.” It is demanding: “A thing is right when it tends to preserve the integrity, stability and beauty of the land. It is wrong when it tends otherwise.” And a land ethic cannot be only an idea of the mind: It must be lived, “for nothing so important as an ethic is ever 'written'.”

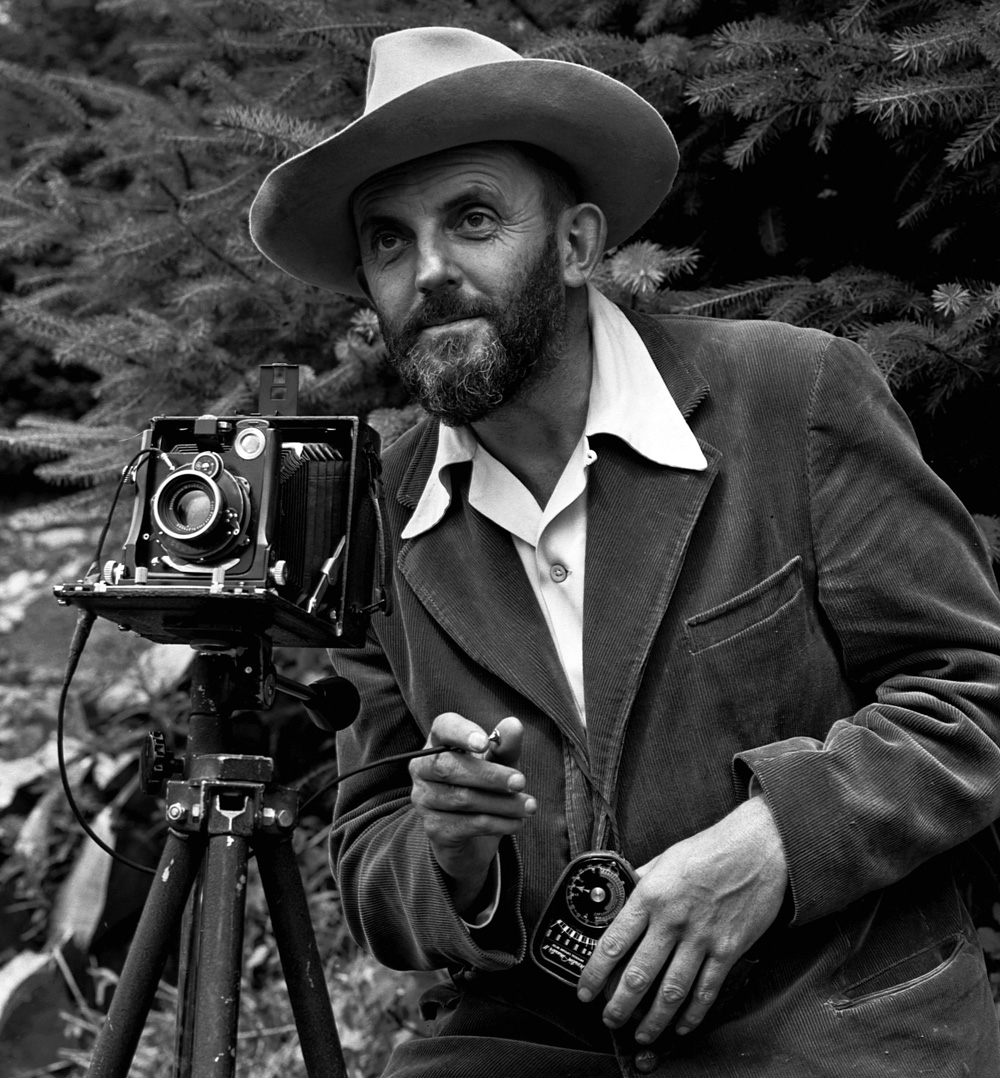

America’s greatest landscape photographer, Ansel Adams was born in 1902 and grew up in San Francisco’s remote Golden Gate area long before the bridge was completed in 1937. As a boy, he reveled in the sand dunes and his hikes to the water’s edge. The great passion of his life, though, was Yosemite Valley and the Sierra Nevada, which he first visited—and did his first photography—at the age of 14. “I knew my destiny when I first experienced Yosemite,” and from then on his life was, as he put it, “colored and modulated by the great earth gesture” of that landscape. He went to the Sierra every year until he passed away in 1984.

Adams became active in both the Sierra Club, where he served as a longtime board member, and The Wilderness Society and wrote a steady stream of letters to newspapers and public officials on wilderness issues. Blessed with boundless energy, Adams, with his distinctive, exacting black-and white images, was giving nationally-noticed shows by the 1930s. He used his images to protect the environment for the first time in the campaign to preserve the upper Kings River watershed and his efforts were critical to the legislation creating Kings Canyon National Park in 1940.

Working broadly throughout the American West and Alaska, Adams’ photographs were used in many conservation efforts and also contributed to the building of a conservation ethic in the post-World War II years. John Sexton, himself a master photographer, said of Adams that “He combined his passion for the preservation of the environment with his passion for photography almost seamlessly. He used his photographic skills to convey his personal excitement for the natural environment, as well as the irreplaceable value of the wilderness experience.” William Turnage, President of The Wilderness Society and author with Adams of The American Wilderness, one of the best of the many collections of Adams’ work, also explained how Adams’ artistry and activism blended together: “When people thought about the national parks or nature itself, they often envisioned them in terms of an Ansel Adams photograph…. He created a sense of the sublime magnificence of nature that infused the viewer with the emotional equivalent of wilderness, often more powerful than the actual thing.”

Late in life, Adams received many honors, including the Presidential Medal of Freedom, America’s highest civilian award, for "his efforts to preserve this country's wild and scenic areas, both on film and on Earth. Drawn to the beauty of nature's monuments, he is regarded by environmentalists as a national institution. It is through his foresight and fortitude that so much of America has been saved for future Americans.” Shortly after his death, Congress created the spectacular, 230,000-acre Ansel Adams Wilderness Area, which includes the Minarets and is contiguous to his beloved Yosemite.

The nation’s oldest environmental law firm, Earthjustice’s origins trace back to the mid-1960s when two volunteer attorneys began work on the Mineral King controversy. The Walt Disney Company had targeted this magnificent, remote high-Sierra valley in California as the site of a large ski resort, and the Forest Service gave the go-ahead. In 1971, with the case heading to the U.S. Supreme Court, the attorneys officially created the non-profit Sierra Club Legal Defense Fund. (In the 1990s, the firm, which had always been independent of the Sierra Club, changed its name to Earthjustice.) The young organization succeeded in having the Mineral King case sent back to the trial court and the ski development project was soon dropped; the litigation brought the matter to light and strong public opinion in favor of keeping the Mineral King Valley pristine made the project politically impossible.

Ever since, Earthjustice has done first-rate legal work for the environment, sometimes representing—always without cost—national organizations such as the Sierra Club and The Wilderness Society and on other occasions litigating on behalf of individuals and regional and local environmental groups. Earthjustice, the largest nonprofit environmental law firm, has nine regional offices and has handled cases in all corners of the country. The firm also pays heed to “environmental justice” and brings cases on behalf of African-American and Hispanic communities and Indian tribes that have been disproportionately affected by bad environmental practices.

Earthjustice has taken on virtually every kind of environmental issue one can imagine. David Guest narrates the struggle to protect Florida’s lakes, rivers and swamps from the scourge of toxic algae outbreaks caused by agriculture and industry. In Alaska, attorneys have brought campaigns to protect the elk, polar bears, and other wildlife of the Arctic wilderness from climate change and oil spills. Earthjustice joined with the Lower Elwha Klallam Tribe, other environmental groups, and the Park Service to bring back the Elwha River’s great salmon runs by the removal of two dams on the Elwha River on the Olympic Peninsula. It is the largest dam removal in American history. The firm has also worked to protect the wonderful and threatened orcas, the so-called killer whales renowned for their acrobatic leaps and complex social patterns, and also articulates the joy and deep commitment that she and other Earthjustice attorneys bring to their work.

Of course, there are a number of other nonprofit environmental law firms doing excellent work, and environmental lawyers in federal, state, tribal, and local government offices have made major contributions. Honoring Earthjustice in this manner in no way diminishes their many accomplishments but rather is a way of acknowledging how critical environmental law is to protecting and healing the environment.

A true pioneer in the mid-19th century, Thoreau was the first American to articulate the value of the pure natural world. An influential writer, his words resonated with opinion leaders and the general public alike and laid the foundation for the explosion of conservation policy that began a generation later.

Before Thoreau, there was no conservation because there was no perceived need for it. Bringing full civilization to the new nation was just a matter of taming nature, and America seemed inexhaustible in its vastness.

In 1845, he moved to a small house on Walden Pond, about two miles outside of Concord, Massachusetts. “I went to the woods because I wished to live deliberately, to confront only the essential facts of life…. I wanted to live deep and suck out all the marrow of life.” In 1854, he published Walden, or A Life in the Woods, in which he recounted his two years at the pond and reflected on the value of living a simple life in nature. This reflected the core philosophy of Thoreau and Ralph Waldo Emerson, the other principal figure in the transcendentalism movement, based on the belief that pure nature held transcendent truths.

Thoreau’s most powerful and enduring summons was “Walking,” delivered as a public lecture in 1851 and published, after his death, twelve years later in the Atlantic Monthly. He began by arguing that “The West of which I speak is but another name for the Wild; and what I have been preparing to say is, that in Wildness is the preservation of the world.” He used the word “Wildness,” rather than “wilderness” because he had two notions in mind, the wildness in nature and the wildness—the creativity and bravery—that exists within humans. His conclusion in “Walking” shows how the two meanings of wildness can wrap together: ”In short, all good things are wild and free. There is something in a strain of music, whether produced by an instrument or a human voice,--take the sound of a bugle on a summer night, for instance--, which by its wildness…reminds me of the cries emitted by wild beasts in their native forests.”

Thoreau did not experience anything close to John Muir’s total immersion in the natural world, but he had a broad audience for his bold ideas. American conservation owes much to Thoreau’s trailblazing work, which was one of the influences that led to the creation of Yellowstone National Park in 1872, the first national park in the world and, generally, to the conservation explosion of the early 20th century embodied by TR. And his clarity and unwavering insistence continue to inspire us today.

It was not Abbey’s monkey-wrenching, high-speed chases, and pro-environment tirades that made him such an important voice but rather the fact that he loved the desert Southwest with all his heart, knew the landscape cold, and wrote about it with great skill and utter authenticity. He came from the Pennsylvania Appalachians to New Mexico in the 1940s and immersed himself in the Southwest, eventually writing books such as The Brave Cowboy, Fire on the Mountain, and, published in 1968, Desert Solitaire, one of the great works in conservation philosophy in which he warned of the “industrial tourism” that now plagues the Southwest.

Abbey’s writing is tactile and immediate, and often depicts the small and seemingly insignificant denizens of the desert. He had a favorite juniper—“ragged,” “with a sapless claw”—at Arches National Park where he served as a ranger. He gave his admiration to another juniper for simply making it in the harsh environment: It was “a degenerate juniper tree ... an underprivileged juniper tree, living not on water and soil but on memory and hope. And almost alone.”

Abbey challenged us physically: “You can't see anything from a car; you've got to get out of the goddamned contraption and walk, better yet crawl, on hands and knees, over the sandstone and through the cactus. When traces of blood begin to mark your trail you'll see something, maybe." He challenged us intellectually: “The desert… sharpens and heightens vision, touch, hearing, taste and smell. Each stone, each plant, each grain of sand exists in and for itself with a clarity that is undimmed by any suggestion of a different realm…. Only the sunlight holds things together. Noon is the crucial hour: the desert reveals itself nakedly and cruelly, with no meaning but its own existence.”

Edward Abbey gave us the desert. He implored us to understand it, love it, and protect it. Ever since, conservation has made great strides in the desert Southwest. Much more progress will come, for now we are clear on what we have to save and what we have to lose.

A member of a leading Flagstaff, Arizona ranching family, Babbitt is a lifelong environmentalist and committed outdoorsperson who has taken many backpacking trips in the Grand Canyon area. He served as Arizona governor from 1976-1987, successfully pushing through several wilderness designations and insisting upon comprehensive state legislation protecting the state’s groundwater aquifers.

President Clinton named him Secretary of the Interior and he served from 1993 through 2001, compiling a record equaled only by Stewart Udall. An intellectually curious geologist and lawyer, Babbitt took a hands-on approach toward the issues that captivated him most. Ignoring virulent opposition, he launched a new era in wildlife protection by reintroducing wolves in Yellowstone in 1995 and 1996, displaying the grace and compassion that our nation can sometimes summon in the name of conservation. He later reintroduced California condors, with their six-foot wing spans, in the Grand Canyon area. He became convinced that Colorado River endangered fish species in the Grand Canyon needed high Spring flows from Glen Canyon Dam to flush out artificially high sediment loads and create better habitat. He went ahead with the high flows, which represented the river’s natural regime, despite vigorous opposition from energy companies.

Babbitt also was the point person for Clinton’s ambitious program to protect expansive areas of federal lands as national monuments under the Antiquities Act; this 1906 statute has been a favorite of presidents, especially Theodore Roosevelt, since it allows for unilateral presidential action without any approval by Congress. Babbitt submitted to Clinton proclamations, all signed into law, for 20 new monuments and three expansions of existing monuments totaling nearly 8 million acres. The creation of the Clinton-Babbitt monuments, which protected some of the most contested and magnificent western landscapes, stands as one of the highest points in conservation history.

In all, Bruce Babbitt, with his love of the land, scientific background, knowledge of history, and experience as governor, came into office with an enlightened and firmly-held vision for the public lands based on protection and restoration of large landscapes. Then he acted upon that vision. He put it this way: “Restoration is about having the power to visualize, to say that we can imagine a landscape that we don't see today, that we can create, or recreate, a landscape that was seen by Lewis and Clark, Kit Carson, and our forebears. We can look to the past, and by understanding the past, visualize the future. And then engage communities and conservationists in the act of restoration. That has a lot of magic and power.”