Shannon Tobolov

Shannon Tobolov

In a rolling grassy landscape reminiscent of the Scottish Highlands, I stop and let out a startled gasp. Just 20 feet in front of me, a kangaroo stands on the trail and looks casually at my hiking partner and me. Then, as if slowly transposed upon the landscape, a mob of its curious brethren emerge from the heavy mist. Lazily shifting their gaze from us to the grass, they put their heads down and graze as we hike past, rather unfazed by our presence. Though the beaches of Australia’s Great Ocean Walk are astounding for their isolation and beauty, it is this memory that will forever remain etched in my mind as the highlight of our coastal hike.

Some years ago, my best friend Shannon met an Australian guy on a beach in Thailand. Long story short, she is now happily married and living in Melbourne, a literal world away from our Vancouver, B.C. home. Our friendship, which began at 6 years old climbing trees and building forts, had grown into a lifetime of shared adventures, including months in India and a Kilimanjaro summit. Given our history, I’ll admit that I was mildly concerned that Australia’s Great Ocean Walk would be slightly bland and overly touristy by comparison. But that concern was put to rest immediately, and instead it proved to be the perfect backdrop for reminiscing about our childhood and catching up on our adult lives. The landscape was breathtakingly varied and the beaches the most stunning I’ve ever laid eyes on, and the only crowds came in the form of tropical birds, wallabies, kangaroos, and the occasional echidna or koala.

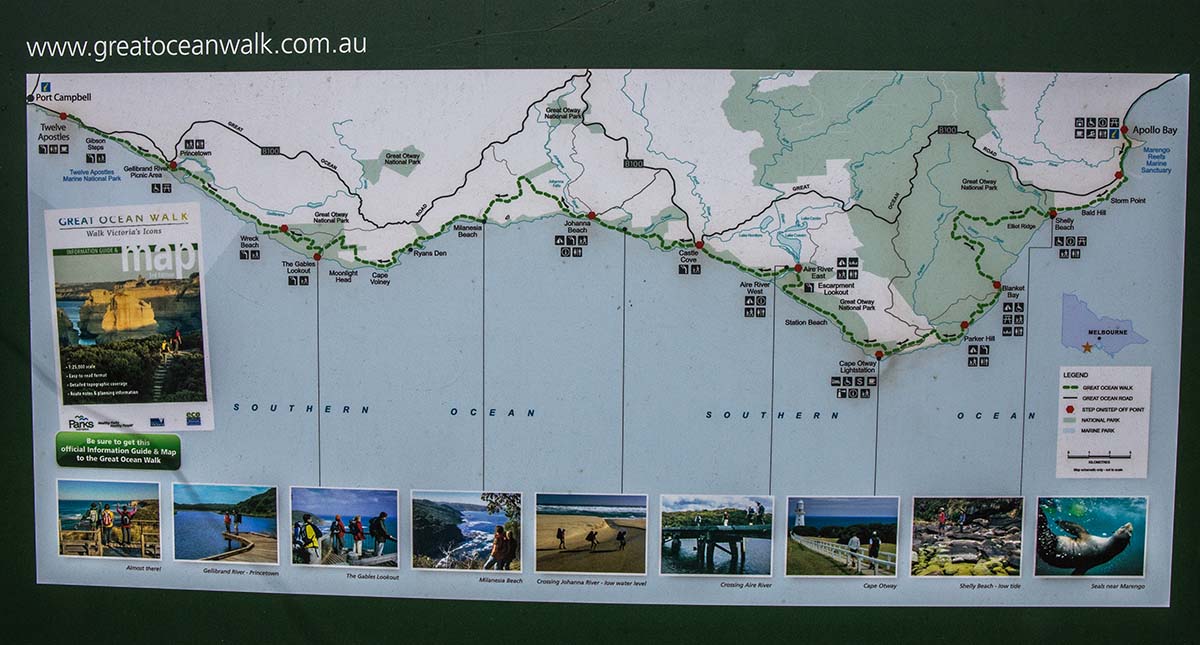

The Great Ocean Walk (GOW) loosely follows the famous “Great Ocean Road” and joins Australia’s Apollo Bay to the iconic and touristic Twelve Apostles, which are seven limestone stacks off the coast. The roughly 100-kilometer string of beautifully maintained trail meanders along a coastline of ever-changing beaches with golden sand, crashing surf, and turquoise waters, and through fragrant eucalyptus forests and hardy bonsai-like coastal shrubs. It is typically walked in eight days and can be tackled self-supported or with the assistance of a tour company that can provide varying levels of support, including shuttles, supply drops, and accommodation. Short on time but with plenty of energy, Shannon and I decided to commence partway through at the Cape Otway Lightstation to cover the last 67 kilometers of the trail (typically done in five days) self-supported and over the course of three long days.

We park our car at the Twelve Apostles’ visitor center and jump in our pre-arranged shuttle for the hour and a half drive to the Otway Lightstation. Our driver spiritedly chats with us about the recent fires that have devastated parts of Australia and the good ole’ days before the Great Ocean Road was paved. We pass rural farmland with kangaroos grazing in the distance, swerve around brazen wallabies hopping across the road, and minutes before reaching the trailhead—in the midst of a discussion about reading tides and swells—screech to a halt as our driver shouts “there’s one!” and points at a fuzzy lump in a tree. We jump out to watch a very cute koala sleepily eying us from the branches. A KOALA! It seems the perfect way to start a hike in Australia.

At the Otway Lightstation, we launch down the well-marked and maintained trail, excited to begin our journey. As though I need a reminder that I’m not home in the PNW, I round a corner and am startled by a wallaby standing on the trail. Paranoid of snakes, Shannon immediately assumes my sudden stop is a snake sighting, and a fearful yelp jumps from her lips. The adorable wallaby is unaffected by the crazy tourists and causally hops off. Similar scenarios occur often throughout our hike: fat blue-tongued lizards, wallabies, and an even an echidna manage to startle whomever happens to be leading, evoking a stronger adrenaline rush for the follower who always assumes a threatening snake. Particularly abundant on this section of the walk, wallaby sightings soon become as casual as seeing a squirrel in the PNW. Hear something in the bushes? It’s a wallaby. See something run or jump across the path? It’s just a wallaby. Feel like you’re being watched? Oh, look—it’s a wallaby. This is not something a Canadian soon gets used to, and every single time one appears, I gasp in wonder at their awkward exoticness.

My calves immediately notice that the hills are steeper than anticipated, as I had mistakenly assumed that a walk that follows a coastline would be almost level (I should have known better, as our local West Coast and Juan de Fuca trails are anything but flat). Despite my surprise, I am delighted by the variety of pitch and terrain as the trail meanders up and over cliffs before descending to the golden sands of Station Beach.

The morning mist has burned away, and the strong sun forces us to reapply sunscreen often on our sandy skin and seek shelter in scrubby trees along the trail. The frequent views back to Otway Lightstation remind us how far we’ve come, and emerging sights of our final destination lure us on. We descend to the Aire River wetlands and are happy to empty the sand from our shoes and rest in the shade near the campground at Aire River. Lucky for us, there are several families of koalas who live in the eucalyptus trees near the picnic tables, and we watch them graze (oh so slowly) on the trees’ leaves before we continue on the next stretch of trail toward Johanna Beach.

The trail turns slightly inland, through mounds of unearthly spinifex, and then returns to the coast for views of the turquoise waters and rugged and tortured cliffs. We chat and catch up on each others' lives, then walk in silence taking in the views, sounds, and fragrances. Our hike continues through heathland and forests of manna gums and grass trees before dropping down to Johanna Beach.

After a day of undulating terrain, the last 2 kilometers of our walk are along the sandy beach —always a blessing and a curse. The ocean had looked inviting from a distance, but once on the sand, it’s immediately clear that even wading in the water would be unsafe. We settle for bare feet and sand between our toes. Hiking in the sand with a pack is effortful, though Shannon’s beach life in Australia has somehow trained her to make it look easy. And despite my weariness, I’m happy to be so close to the crashing waves of rough open ocean. I’ve been to the beaches of Oregon, Hawaii, and B.C.’s west coast, but this feels even more powerful and wild. The continent of Australia is truly isolated.

We climb the stairs out of Johanna Beach, and heeding our shuttle driver’s warning that some hikers mistake the car-camping sites here for GOW sites, we continue a ways further and up to a stunning bluff overlooking the coastline. Here, we set up our tent and settle into dinner with impeccable timing—the clouds soon become dark and a torrential rain pelts the corrugated roof of the shelter that inhabits each GOW campground. We chat with a Canadian couple who are already hunkered down, and they note that we are the first hikers they’ve met in three days on the trail. Ultimately, these two remain the only hikers we see on our journey.

The rain subsides, and streaks of sun filter through the clouds as we enjoy evening tea and settle into our tent. Sticky from the humidity, sunscreen, and salty ocean air, we are both lulled into a deep sleep by the echo of crashing waves below.

As we enjoy our coffee and breakfast, the rain that started during the night continues with no sign of breaking, making us grateful for the views we had the previous evening. As hardy Vancouverites, we are not discouraged by the rain. Instead, buoyed by the success of completing 24 kilometers on our first day, we decide to aim for 27 kilometers today. With our soggy tent packed, we set off and soon find ourselves surrounded by a mob of curious kangaroos. Though there’s a muscular male who appears to bench press in his spare time, they pose no threat as we weave through their group. It’s thrilling to see so many kangaroos, and I still get a stupid grin on my face when I think of this scene. Koalas, wallabies, kangaroos… check, check, and check.

Soon after the bucolic rolling hills, the trail joins the gravel of the Old Coach Road and gently climbs through a eucalyptus forest. The GOW signs become sparse, but fresh boot tracks in the mud, as well as a local’s “water stop," reassure us that we have not missed a fork. The rain continues and enhances the powerful fragrance of eucalyptus and damp earth with hints of citronella. If I were a candlemaker, this would be my target cocktail of scents. We lose our well-earned elevation as we duck down to rugged Milanesia Beach, the shrubbery becoming similar to that on our west coast. Because it’s late summer on this side of the equator, the blackberries are abundant. We gorge on the sweet fresh fruit under the watchful eyes of large kangaroo.

The hike out of Milanesia Beach is steep, but the blackberries and breathtaking views towards Cape Otway provide us with excuses to stop often. After a few more surprisingly steep ascents and descents, often aided by sloped steps carved into the hillsides, we stop at the Ryans Den Campground, enjoy our lunch, recharge, and carry on towards Devils Kitchen.

From Ryans Den, the trail continues through varied flora, with undergrowth consisting of grass trees along the open bluffs and lush tropical ferns under the canopy of eucalyptus trees. Because we will be passing Wreck Beach during high tide, we have no option but to take the inland trail for this section. Lengthy boardwalks—built to help prevent the spread of cinnamon fungus—make the trail fairly easy, but over 50 kilometers in two days has made us tired and sore. We’re happy to see the shelter and water tank that signal our arrival at the Devils Kitchen campsites. The only ones there, we get our pick of sites and settle on #8, the only plot with an ocean view. We let our soggy tent dry while we enjoy dinner. Unlike the previous evening, the temperatures are cool, and we don our beanies and insulated layers before turning in for the night. Again, we both sleep soundly, as the waves crash against the shore below us.

We awake to the promise of clearing skies and emerge from our sleeping bags with excitement for the last day of our journey. Because we will be finishing a day earlier than anticipated—and because it’s Shannon’s birthday—we treat ourselves to a dinner for breakfast, preferring pho to bland porridge. This day is a stunner. Whereas on the previous two days the trail often skirted inland, much of our final day follows the coastline. Cliffy ocean views dominate from the start.

A couple hours in, we see the wetlands near Princetown and descend before heading back up along the sandy trail. On this section, I round out my wildlife viewing as we almost trip over an echidna, which looks like a very cute large long-nosed hedgehog. We get our first glimpse of the Apostles in the far distance, and knowing that we have plenty of time, stop for a break. Arriving at the Great Ocean Walk viewing platform, we see our first tourist, who literally warns us to get ready to enter crowds. Re-entry is always difficult, and as the Apostles continue to dominate our view, I’m tempted to avoid the boardwalks that provide the best views. Shannon is quick to point out that it would be ridiculous for me to have come all this way and not see these icons because of my low tolerance for crowds. I am grateful for her gentle nudge, as glimpsing the limestone pillars and the impressive cliffs is well worth it. And, let’s be honest, we did need to commemorate our walk with a selfie.

I am admittedly a mountain person and the alpine air feeds my soul, but it is hard to deny that beaches and ocean can be stunningly beautiful and mesmerizing. Victoria's southwestern coast is the most gorgeous I’ve seen, complete with golden sand, crashing surf, jagged cliffs, turquoise waters, and very few people. While the visual beauty is undeniable, I found myself incredibly struck by the sounds, fragrances, and sensations that flirted with my other senses. There was the omnipresent bass of crashing ocean waves, accompanied by the treble of tropical birds. Fragrances ranged from salty ocean mist to an earthy herbal scent with undertones of a distinct lemon fragrance, and the sun and misty wind against my skin is a feeling that can only come from the ocean. All of these sensations coexisted in a way I have not encountered on other multi-day adventures. The cute and interesting animals and beautiful exotic birds round out the experience of a truly unforgettable, and Great, ocean walk.

If you’re traveling from outside Australia, you’ll want to fly in and out of Melbourne. Keep in mind that travelers from many countries (including Canada and the U.S.) will require an e-visa, which currently costs $20 AUD (about $14 USD at the time of publishing) and is simple to obtain online. As always, it is best to confirm entry requirements before any international travel.

From Melbourne, it’s a 2½- to 3-hour drive to the Twelve Apostles Visitor Centre, the standard ending point for the Great Ocean Walk. If you have your own vehicle, you’ll leave it here (to reunite with at the end of your journey) and take a shuttle to the start of your hike. The Great Ocean Walk’s official website provides numerous links to guide and transportation companies, and this is where we found our shuttle (Great Ocean Road Shuttle). The cost from Twelve Apostles Tourist Centre to the Cape Otway Lightstation was $120 AUD (roughly $83 USD).

If you do not have a vehicle to drop, you can go directly to the starting point at Apollo Bay (also a 2½-hour drive from Melbourne). The Canadian couple we met told us that they were quoted over $800 AUD for a taxi from Melbourne to Apollo Bay, so they opted for public transit (the V/Line train and bus). Australia also has a well-used app called “Airtasker” where you might be able to find a moderately priced ride.

Although the Great Ocean Walk can be done year-round, the most popular times to go are spring (late September to late November) and fall (early March to mid May), avoiding the storms of winter and heat (and bushfires) of summer. Springtime is the prime season to enjoy wildflower blooms and fall offers the most stable weather; conversely, it's common to find moderate temperatures (and minimal crowds) during the summer too. No matter when you go, you'll want to be prepared for all manner of weather—after all, Victoria's coastal region is famous for its “four seasons in a day.” During our hike in February—the height of summer—daytime temperatures ranged from about 50 to 85 degrees Fahrenheit, and we experienced fog, rain, sun, and everything in between. Because of the large variation in weather, a waterproof tent and ample layers of clothing are imperative regardless of the season. For more on this, see “What We Brought” and “What We Wore” below.

Most Great Ocean Walk travelers will choose to stay in the hike-in campsites along the trail. Each campsite has a three-walled shelter and access to pit toilets and rainwater tanks. Keep in mind that wild camping is not allowed, and campsites must be reserved ahead of time through the official GOW website.

If you’re looking for a more civilized experience—or perhaps want to break up a week of camping with one night inside—it is possible to find accommodation in guesthouses, hotels, and hostels along the way. If you choose to do so, take note this will add mileage on to your hike (the couple we met stayed at a guesthouse but noted that it was 3 km off the trail, thereby adding 6 km to their hike). On the other hand, numerous tour companies can provide various levels of support, including shuttles to and from accommodation off the trail.

There is virtually no natural water source along the Great Ocean Walk. For those accustomed to mountain streams, this will take some planning—you’ll want to load up each morning at the campsite and replenish at any sites you stop throughout the day (tour services also provide water drops). Each campsite has rainwater tanks that are dependent on rainfall, but it’s important to keep in mind that Parks Victoria does not guarantee water anywhere (you can call the park before you start and get updated info on the status of each tank). And take note that the rainwater is not treated, meaning you’ll want to use a filter or purifier to clean your water before drinking.

We should note that there are a few restaurants and small grocery stores along the trail, most notably at Apollo Bay (the beginning of the route), Cape Otway, Lavers Hill, Princetown, and Port Campbell (the end of the route). However, food supplies are very limited and we do not recommend relying on these stores and restaurants too heavily (particularly those in the middle of the trail). Eight days of food can be a lot to carry, however, and for this reason many hikers will stage resupplies along the way, whether with the help of a tour company or by their own means (it's important to always use sealed containers so animals do not get into your stash).

The Great Ocean Walk is relatively well-marked with signposts along the way, but you’ll still want to carry a detailed map. We found the Great Ocean Walk Information Guide & Official Map (1:25,000) and the Great Ocean Walk Official Walker’s Maps Booklet to be helpful. If you choose to use your phone for navigation (apps like Hiking Project, Gaia, and Topo Maps are some of our favorites), keep in mind that mobile phone coverage is not consistent along the trail. My international phone was better because it searched for any carrier, but if you have to choose a local carrier, Telstra tends to have the strongest signal. Regardless of your coverage, you’ll want to make sure to download your maps to your phone before you embark.

This should go without saying, but it’s important that hikers stay on the trail and use boardwalks when applicable. The Great Ocean Walk, like most hiking routes, is increasing in popularity, and all hikers can do their part to keep impact to a minimum and preserve the coast’s wild nature. Parks Victoria also provides hiking boot washing stations to help prevent the spread of cinnamon fungus, which kills native plants. Be sure to stop and use these stations whenever you see them along the trail. And as always, remember all Leave No Trace practices. Don't take shells from the beach (they're pretty, we know!), use designated toilets, and pack out what you pack in.

As far as hikes go, the Great Ocean Walk is easy to moderate. The trail is simple to follow, nicely graded (there are only a few sections with very steep pitches), and ample campgrounds allow you to keep your mileage between 6 and 9.5 miles each day. That said, it's important not to underestimate the strain that eight days of hiking can put on a body, especially if you've never taken on such an endeavor. It helps that the location of the trail makes it easy to prearrange resupply spots, which means you don't need to travel with the weight of over a week of food on your back.

Snakes

If you’re hiking the Great Ocean Walk in the summer months, there’s a (very low) chance you’ll glimpse a snake (despite our constant vigilance, we saw none). The three main varieties of snakes in this part of Australia include the White-Lipped Snake (not very dangerous), the Lowland Copperhead (slightly more dangerous), and the Tiger Snake (very dangerous). It’s important to remember that snakes don’t like people, so if you make an effort to avoid them, they’ll make an effort to avoid you. In the unlikely event that you are bitten, the most important thing you can do is evacuate and seek professional help immediately (there are a variety of theories regarding how to manage venom, and we are not qualified to state which is the most effective). In the end, we’ll leave you with this: no one should opt not to do the Great Ocean Walk for fear of snakes. Snake bites along the trail are incredibly rare, and not antagonizing snakes can go a long way to prevent harm.

Fire

The bluffs along the Great Ocean Walk are at a high bushfire risk during dry and hot weather. Before you begin your trek, we recommend checking in at the visitor center to get up to date on current conditions and learn about what actions to take if you see a fire. We found the “VicEmergency” app to be helpful for updates on fires or other incidents along the walk, but keep in mind that you’ll need mobile coverage to access this information (which was spotty). Campfires are not permitted at any hike-in campsites along the Great Ocean Walk (some car-camping areas allow them, but you’ll have to provide your own firewood). And on Total Fire Ban Days (when fire danger is very high), the National Park asks that you only use your backpacking stove for meal preparation and be sure to have a roughly 10-foot radius clear of flammable material and 10 liters of water nearby to douse a flame.

Tides

It is critical that hikers are aware of tides and swells for beach crossings, particularly for Wreck Beach (which is impassable at high tide). The Australian Government’s Bureau of Meteorology marine site notes tide times for Port Campbell (close to the Twelve Apostles) and Apollo Bay, but some estimation is required for specific beach information (there is a two-hour tide-time difference between Apollo Bay and the Twelve Apostles). Our shuttle driver recommended WillyWeather, which we found easier to use as we could look up specific beaches for tide and swell information. Note that there are several beaches called “Wreck Beach,” so be sure to select the one in Victoria.

Swimming

Most hikers won’t even consider swimming along the Great Ocean Walk—not only is the ocean rather uninviting, but the surf is no joke and full of strong currents and rips. But if taking a salt-water dip is tempting, consider this warning on the GOW official website: Beaches nearby to the Great Ocean Walk are generally remote with limited or no mobile phone signal or rescue vehicle access. If you swim on unpatrolled beaches you may die. In other words, we recommend saving your ocean dips for elsewhere.

Shannon and I decided to go fairly light for our trek, which enabled us to travel 67 kilometers in three days. For a sleep setup, we shared the Big Agnes Copper Spur 3 Platinum tent, which has a trail weight of only 2 pounds 15 ounces (and can be divvied up between two packs fairly evenly). We both slept on a Therm-a-Rest Neo-Air XLite pad and had matching Western Mountaineering Summerlite sleeping bags (32˚F; 1 lb. 3 oz.). For our stove, we carried the MSR Reactor, which does well in stormy conditions and proved to be a faithful companion for our breakfasts and dinners. We treated the rainwater at each campsite with the MSR Guardian, a purifier and filter that is fast, reliable, and even self-cleaning. To carry all our supplies, I used the Hyperlite 2400 Southwest and Shannon carried the Osprey Eja 48, both ultralight packs that manage to combine comfort with a lightweight build (but should not be loaded down with much more than 30 lbs.).

For the hike, I started my layering with a t-shirt (Lululemon) and shorts (Oiselle), which was ideal for building up a sweat in warm temperatures. I carried the lightweight Arc’teryx Nuclei FL for insulation, and I was grateful that I opted for a synthetic jacket over down for the wet weather we encountered. Arc’teryx’s Beta SL Hybrid hardshell kept me dry in the rain and was breathable enough to wear even while hiking. I also brought along a pair of prAna tights for evenings at camp, and these proved to be great companions in my sleeping bag during the chilly nights.

On my feet, I wore the La Sportiva Bushido II, my favorite trail runner that’s great for rugged trails and supportive enough to handle a 30-pound load on my back. Those carrying a heavy eight-day load should consider more supportive hiking shoes or boots (like the Salomon X Ultra 3 or Merrell Moab 2 Mid), and I recommend opting for the non-waterproof variety (which will dry out much faster than waterproof footwear). I brought along ankle socks, but I would instead recommend long socks to keep out sand and grit, and the most particular hikers will likely appreciate ankle gaiters for added coverage.