All good plans start with a wild idea, but this one might just take the cake. Back in the spring, Kaytlyn—who I’d never met at the time—approached me with an ambitious proposal. She wanted to link up a series of North Cascades high routes on foot, starting somewhere near the Canadian border and finishing at the southern end of the park. Each of these five traverses take the average mountaineer anywhere from three to seven days to complete, and Kaytlyn wanted to do them all in a push.

She thought it could be done in a week.

It goes without saying that I responded with an emphatic YES. I don’t think I would have ever personally drummed up the ambition to take something like this on, but—even though I barely knew her—something about Kaytlyn’s approach was incredibly confidence inspiring. She was calculated, organized, and skilled at whittling down the impossible into manageable parts: we’ll recon this section, scour the internet for beta on that section, hassle our friends (and friends of friends) for their secret and hard-won gpx files to fill in the gaps. We’ll slowly piece together a line across our shared map. And then, with our gear prepped and our crew at the ready, we’ll get down on our knees and beg for a unicorn of a window, when weather and conditions and schedules and health align.

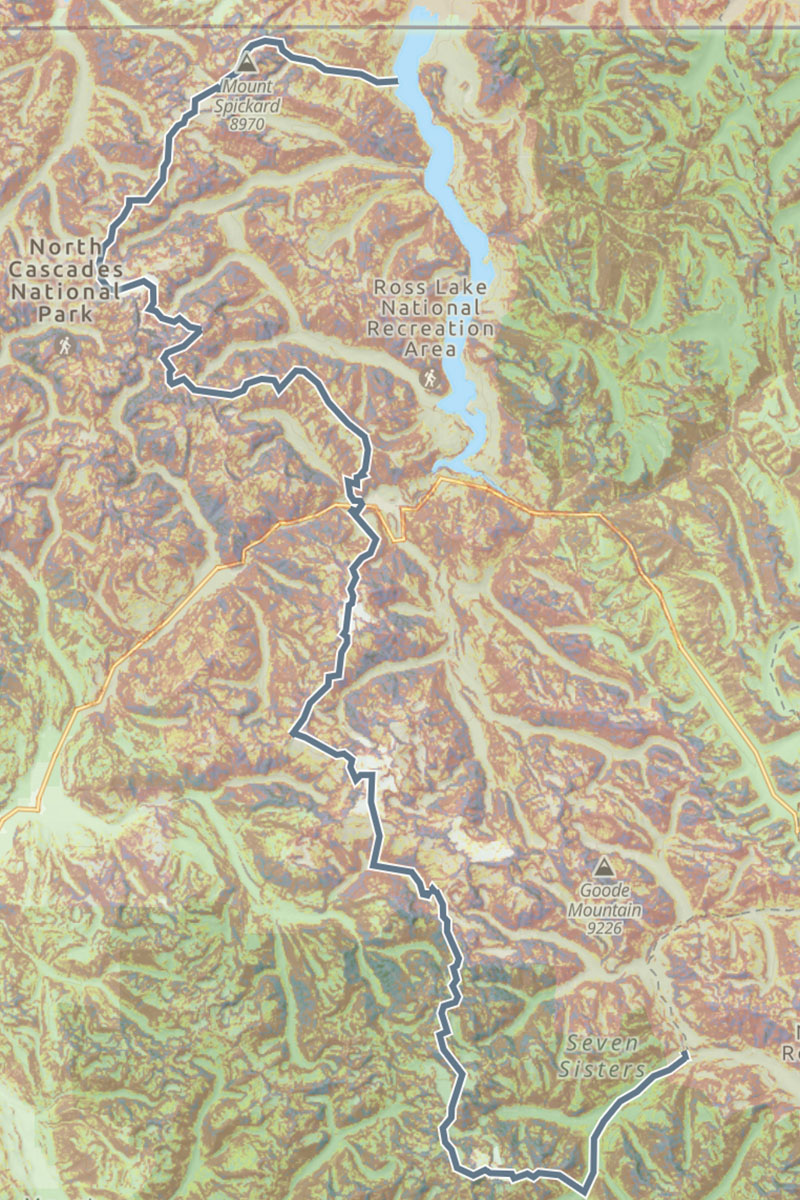

We embarked on the afternoon of July 23, starting with a boat ride up Ross Lake to Silver Creek, just a few miles south of the Canadian border. I had just recovered from Covid; Kaytlyn still had some time before needing to shift her focus to UTMB, a premier ultramarathon in Chamonix. The snowpack was unseasonably high—making for easy travel—and the forecast showed seven days of almost-perfect weather. We had our window.

The North Cascades high country is unlike anywhere in the Lower 48: It’s incredibly steep and rugged, difficult to access (often requiring hours of bushwacking), and almost void of trails—our route included glacier crossings, sections of technical rock, and painfully slow navigation. We set our watches to record in “trail run” mode, but ran so seldomly that we made a habit of calling it out each time we did. In the end, it’s hard to know what to call this style of travel—it’s neither mountaineering nor trail running, but it’s high on shenanigans and certainly nails the “ultra” part of ultrarunning. Somewhere along the way, we started calling it ultraneering, a term borrowed from one of Kaytlyn’s friends that probably means nothing but somehow feels accurate. Whatever you name it, we were moving quickly through the mountains.

In the aftermath, I find it difficult to write about any one section, day, or moment of the traverse. But if a journey is a sum of its parts, what did this one contain? There was snow and scree, the odd boulder field, rock slab, or heather-laden slope, and more snow and scree. There were gracious passageways through slide alder, docile frozen lakes, and rolling ridgelines. There was tree rappelling and steep snow descents and broken crampons. There were times when it felt like we might fall off the tightrope of our big idea, and there were moments of calm: watching the last light color the Chilliwack range from our camp near Luna Peak, the warmth of a hot water bottle in our shared sleeping bag. Iced lattes at Azure Col, the lone deer at the toe of a glacier, and that peaceful acceptance that comes after benightment, when darkness is no longer a threat but a companion.

And there was, looking back, a clear organization to our week-long journey. During the first half of the traverse, it was just Kaytlyn, myself, and the rugged and rarely traveled ridgelines of the far-north Cascades. We were incredibly focused—navigation was convoluted, the terrain was steep, and there was a lot of ground to cover. For a day and a half, we were completely surrounded by a cloud; just when the sun started to peek through, the inhospitable Picket range came into view. On the third day, it took us over 19 hours of constant travel to cover just 16 miles. We pitched our tent in the wee hours of the morning and collapsed on our half-inflated sleeping pads, our bodies finally starting to absorb the shock of the effort.

At times, I grappled with the enormity of our plan, but I didn’t need to look far for belief: As resilient as they come, Kaytlyn remained positive, approaching each obstacle with composure and a strong can-do attitude. Put together, she and I had almost three decades of experience traveling in the North Cascades, a subconscious compilation of skills, intuition, and persistence that we tapped into throughout our time on-route. No amount of preparation can make the mountains easy, but there was a certain flow to our movements, as if we were doing something for which we’d unknowingly trained our whole lives. Little by little, we picked away at our line across the sky—step step, drink water, eat food, crampons on, crampons off, step step. Chop wood, carry water. We were fully immersed in the moment.

The sun came out halfway through the northern section, but in my memory it only shines on the latter half of the journey. There was a sacredness to the first leg: the intense focus, the desolate terrain, and the intimacy that comes from being the only person to witness the other’s experience. But our tense minds and bodies were ready for a shake out, and our friends were more than happy to help. We were joined by as many as five others on the oft-traveled Isolation and Ptarmigan traverses, and then over the shoulder of Dome Peak and onto the PCT. Our packs were lighter, the terrain gentler, and the finish line closer with each step. It almost felt like we were on a victory lap.

Mid-day on July 30, after almost seven days of near constant travel, Kaytlyn and I—along with our friends Nick, Steven, Michael, and Ely—arrived in Stehekin, a tiny town at the head of Lake Chelan and near the southern end of North Cascades National Park. My body was tired, there were dark circles under my eyes, and my feet and legs were swollen with fluid. My stomach was growling, my teeth hurt from eating too much sugar. In the quiet moments, I often caught myself drifting off in a blank stare.

But I also had the feeling I was finishing a book that I didn’t want to end. For a full week, Kaytlyn and I had been wholly consumed with forward motion. There’s no denying that what we had just accomplished was incredibly contrived—people put forth effort and suffer for far more valiant causes—but I felt enamored with the outcome. We created a game, with conditions and constraints, and then we played it, just for fun. For the pure exaltation of it. What was outside ceased to exist, for the while, and we were characters in our own plot, attempting to pull off our big idea. And the result felt significant: A precious partnership, the testing of minds and bodies, a greater understanding of the mountains, and a fan team of friends and family that got to unite in the process.

All told, Kaytlyn and I had traveled 124 miles down the proudest spine of the North Cascades, ascending (and descending) about 59,000 feet. And just as Kaytlyn had speculated, we had done so in a week. Many have come before us—including a husband and wife team in the summer of 1990, who traveled roughly the same terrain in 28 days (summiting 19 peaks along the way)—and many are surely to come. Perhaps what we did will find itself in the canon of North Cascades history, but more likely, our accomplishment will fade away into the deep valleys between those hills. Like most games—which mean nothing and everything all at once—the outcome matters far less than the act of playing.

In a continuous push, Kaytlyn and I linked up the following established traverses: the Redoubt-Whatcom High Route, the Northern and Southern Pickets, the Isolation Traverse, and the Ptarmigan Traverse (over Dome and Gunsights, exiting onto the Pacific Crest Trail near Stehekin).

We are far from the first people to cover this terrain, and we poured months of research into maps, trip reports, Beckey guides, and conversations with others in order to pull it off in the time that we did. The only sections that we did not recon in advance were the start and finish: Silver Creek to Whatcom Pass (Chilliwack Range and the Redoubt-Whatcom High Route) and Gunsight Col down towards Agnes Creek. We'd both done the Ptarmigan Traverse numerous times, had skied the Isolation Traverse in May of 2022, and have been into the Stettale Ridge, Colonial Peak, and Eldorado areas numerous times. Just two weeks prior (while I lay in bed with Covid), Kaytlyn had reconned the Northern and Southern Pickets traverse in 3.5 days (from Little Beaver to Sourdough Trailhead, with her husband Ely and friend Steven), which was absolutely critical to our success.

Trip Stats

Day 0: head start on Silver Creek. 4:52pm start, 3.8 miles, 1700 ft., 2:52

Day 1: Silver Creek to saddle above Indian Creek. 4:54am start, 15 miles, 8,100 ft., 14:23

Day 2: Saddle to (just past) Luna Col. 5:06am start, 15.3 miles, 9,700 ft., 16:24

Day 3: Luna Col to Stettale Ridge. 5:09am start, 16.4 miles, 9,200 ft., 19:16:03

Day 4: (“rest day” part 1) Stettale Ridge to Sourdough TH, 6:39am start, 7.7 miles, 1,200 ft., 3:00

Day 4: ("rest day” part 2) Sourdough TH to Colonial Glacier Lake, 3:39pm start, 7.5 miles, 5,700 ft., 3:54

Day 5: Colonial Glacier to Eldorado TH, 4:56am start, 20.0 miles, 10,000 ft., 14:58

Day 6: Eldorado TH to Gunsight slabs, 6:09am start, 24.7 miles, 12,800 ft., 15:10

Day 7: Gunsight slabs to High Bridge (Stehekin shuttle), 5:24am start, 14.1 miles, 2,000 ft., 7:06

Entry/Exit Points

While there are numerous examples of people crossing the U.S.-Canadian border via the Depot Creek Trail to access the Chilliwack Range, this is technically illegal (we confirmed via a phone call with U.S. Customs). Given our desire to document and share our traverse, we opted for the Silver Creek approach instead. In retrospect, this approach is logistically much easier: The Ross Lake water taxi is accessed off Hwy 20, just a few miles east of the Pyramid Lake trailhead (the start of the Isolation Traverse).

At the time of our trip, Downey Creek (the standard end of the Ptarmigan Traverse) was closed due to hazard trees. We also really liked the idea of finishing in Stehekin: The tiny town is located at the southern end of North Cascades National Park, and the idea of starting and ending with a boat ride felt aesthetically pleasing, as though we were completing a loop. We would recommend this route (if nothing else but for cinnamon buns at the Stehekin Pastry Company). Crossing the Chikamin Glacier and bushwhacking down to Agnes Creek both add some spice to the end as well, which helps keep the final (and comparatively very mellow) section more interesting.

The gear that Kaytlyn and I used is one of the best indicator of the scope of our adventure. We carried a mix of mountaineering and running gear, with an emphasis on traveling as light as possible. Note: our trip was supported by The North Face (Kaytlyn's primary sponsor), so we used TNF gear whenever possible.

Tent: Big Agnes Fly Creek HV 2 Carbon

Sleeping Quilt: Enlightened Equipment Enigma 20 (shared between the two of us)

Sleeping Pads Therm-a-Rest Uberlite (Kaytlyn's was 3/4-length, mine was full)

Stove: MSR Pocket Rocket 2

Pot: MSR Titan Kettle

Water filter: Platypus QuickDraw and Salomon XA Filter Cap

Headlamp: Petzl Actik Core and Black Diamond Spot 400-R

Trekking poles: Leki Micro Flash Carbon and Black Diamond Distance Carbon Z

Backpack: The North Face Verto 27L and TNF prototypes

Helmet: Petzl Sirocco

Harness: Blue Ice Choucas Light

Rope: Petzl Rad Line

Crampons: Petzl Leopard

Ice axe: CAMP Corsa Nanotec and Petzl Gully

Satellite Messenger: Garmin inReach Mini 2

Watch: Garmin Forerunner 945 and Garmin Forerunner 955 Solar

Shoes: The North Face Flight VECTIV Guard

Synthetic jacket: The North Face Summit Series Casaval Hoodie

Wind jacket: The North Face Summit Series Superior Wind Jacket

Rain jacket & pants: TNF prototypes

Photo credit: Steven Gnam and Nick Danielson

Jenny is a senior editor at Switchback Travel, managing our climbing, trail running, backcountry skiing, and women's outerwear sections. She began exploring the mountains of Washington and Southwest B.C. at a young age with her mom, dad, and sister, including family outings up Mt. Baker, Prusik Peak, and along the Ptarmigan Traverse (which, as an 11-year-old, she called "The Death Hike"). Nowadays, she's a sucker for anything light-and-fast, namely because she despises heavy packs and prefers to travel more quickly than the average mosquito.

Jenny is a senior editor at Switchback Travel, managing our climbing, trail running, backcountry skiing, and women's outerwear sections. She began exploring the mountains of Washington and Southwest B.C. at a young age with her mom, dad, and sister, including family outings up Mt. Baker, Prusik Peak, and along the Ptarmigan Traverse (which, as an 11-year-old, she called "The Death Hike"). Nowadays, she's a sucker for anything light-and-fast, namely because she despises heavy packs and prefers to travel more quickly than the average mosquito.